High Court Victories Show that Cultural Beliefs and Practices Count in Climate Cases

Louise Du Toit, University of Southampton; Brewsters Caiphas Soyapi, North-West University, and Louis Kotzé, North-West University

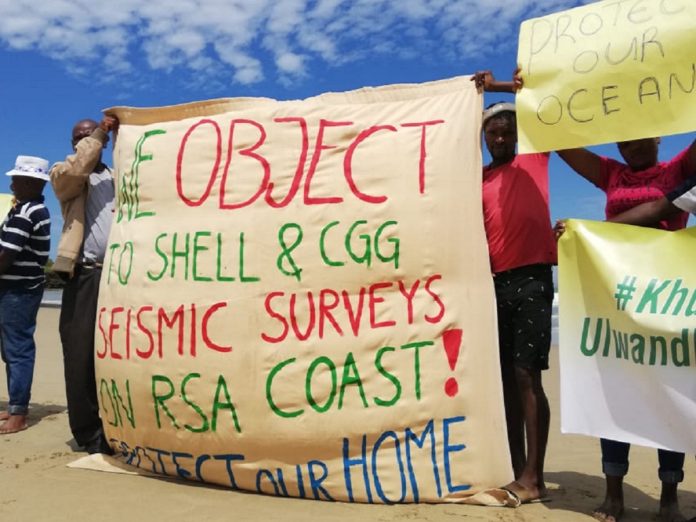

When the Shell petroleum company announced in 2021 that it wanted to explore for fossil fuels off South Africa’s pristine Wild Coast, indigenous communities in the area immediately fought back through the country’s courts.

In two separate cases, the communities successfully challenged Shell. They won both cases, winning an interim interdict to put Shell’s exploration on hold and having the company’s exploration right set aside. Shell is appealing the second ruling on several, largely procedural, grounds; that process got underway in the Supreme Court of Appeal on 17 May this year.

If the Supreme Court of Appeal upholds the High Court’s judgment, this would affirm the Indigenous communities’ rights and interests. If, on the other hand, it overturns the judgment, the exploration right, which was granted 10 years ago, would continue to stand.

Whatever the outcome of this appeal, the two cases are unique. Litigants in other South African climate court cases have mainly relied on environmental arguments. But here, the litigants relied specifically on their Indigenous rights and knowledge to argue why Shell should not be allowed to carry out a seismic survey in their seas.

One of the applicants, Sinegugu Zukulu, is a resident of the Baleni village on the Wild Coast. He is a part of the Amadiba community, which has been living for several centuries in the area. Like other members of his community, Zukulu takes pride in the land on which he lives, partly because his ancestors fought to protect it. In his affidavit, Zukulu said that the land belonged to the community – but the community also belonged to the land:

“The land sustains us and is central to our identity.”

The courts engaged with the communities’ cultural beliefs and practices. They also recognised that Indigenous peoples have a wealth of knowledge related to sustainable living, and that their livelihoods, cultural practices and identities are all threatened by the proposed activities.

We are a team of lawyers who research the space where environmental law meets human rights and constitutional law. We also focus on the political and governance issues that arise within this space, as well as the role of law in mediating the relationship between humans and the environment.

In a recent academic paper we examined the two cases in question. We argue that, in future, Indigenous people’s concerns and considerations could provide a strong basis for climate litigation in South Africa. Using Indigenous knowledge in court to argue against exploration and mining by carbon majors (big oil, coal and gas producers) could potentially contribute to both efforts to protect Indigenous communities and to drive climate action.

The courts’ findings

In October 2021, Shell announced that it would undertake a 3D seismic survey along the country’s south-eastern coast in its search for oil and gas resources. Seismic surveys have the potential to harm diverse marine species and adversely affect humans. They can also contribute to catastrophic climate change. Faced by these threats, activists and affected Indigenous communities brought two applications to the court in 2021 (Shell 1) and 2022 (Shell 2).

In their founding affidavit, the applicants emphasised the importance of the land and sea to their identities, livelihoods and culture. They set out the threats posed by the proposed seismic surveys to their livelihoods and way of life.

They also highlighted that the seismic survey would disrupt their cultural and spiritual relationship with the sea. The applicants told the court that if the seismic survey went ahead, it would have a negative impact on their ancestors and their relationship with those ancestors.

The Indigenous communities argued that, like earlier colonial and apartheid powers, Shell had ignored their right to self-determination, something that is increasingly recognised in domestic and international law. The right to self-determination essentially refers to the right of people to govern themselves without interference from anyone; to determine their own political status; to be free from domination and to have the right to form their own independent state or place to live.

Finally, the applicants were concerned about the seismic survey going ahead without a climate change impact assessment being carried out first. They worried about what the climatic effects might be if the survey revealed hydrocarbon resources.

In the Shell 1 case, the Eastern Cape High Court found that the Indigenous community applicants had met the requirements for an interim interdict against Shell. Shell was temporarily prevented from carrying out the seismic survey. In the Shell 2 case, the applicants successfully established that the consultation process leading to the award of the exploration right was procedurally unfair. The exploration right was set aside.

These were fantastic outcomes for the communities and the environment that sustains them. The greatest significance, we argue, lies in the extent to which the courts engaged with the Indigenous community applicants’ cultural beliefs and practices and their knowledge about sustainability.

Constitutional duty

In the Shell 1 case, the court emphasised the importance of accepting the applicants’ customary practices and spiritual relationship with the sea. The court also emphasised that it had a constitutional duty to protect the holders of such practices and beliefs, and the environment, from the possible infringement of their rights.

The court accepted the applicants’ statements about sustainability and the need for and practice of Indigenous knowledge transfer. For example, it noted that the Amadiba traditional community “practise(s) the customary practices which they have been taught, namely when they fish, they think of tomorrow”. This knowledge about the environment, and ways of living in harmony with the environment, is transferred from one generation to the next.

In the Shell 2 case, the court made similar findings. It emphasised that cultural rights are protected by the constitution.

It accepted the applicants’ belief that:

“the ocean is the sacred site where their ancestors live and so (they) have a duty to ensure that their ancestors are not unnecessarily disturbed and that they are content.”

The court also found that Shell’s proposed measures to limit the impacts of their environmentally harmful activities clearly failed to address potential harm to the communities’ practices and beliefs.

Significance

These cases represent the first time that Indigenous communities in South Africa specifically invoked their cultural rights in climate litigation. This decision adds to a growing body of indigenous-oriented climate litigation cases around the world, such as in Australia and the US.

The judgments are especially noteworthy as they indicate that South Africa’s courts are willing to engage with the cultural beliefs and practices of Indigenous communities, as well as their knowledge related to sustainability.

Louise Du Toit, Lecturer in Law, Southampton Law School, University of Southampton; Brewsters Caiphas Soyapi, Associate Professor: Environmental Change, Faculty of Law, North-West University, and Louis Kotzé, Researcher at the Research Institute for Sustainability Helmholtz Center, Potsdam and Research Professor of Law at the Faculty of Law, North-West University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.